First published at the Times of Israel

The Israeli “Jerusalem Day”, coming up on May 20th, commemorates the 45th anniversary of the 1967 war and the reunification of Jerusalem for the first time under Israeli control.

This is the first of a series of posts that I intend to publish over the coming two months, explaining the issue of East Jerusalem (EJ), a core issue in the Israeli Palestinian/Arab conflict. In this series I will give historical background to one of the world most complicated geo-political problems, while analyzing the Israeli and to some extent the Arab and international policies towards it.

Throughout this series of posts I will refer to the following issues: historical background, the Peace process, the separation barrier in Jerusalem, Palestinian residents of Jerusalem, Zoning and urban planning in East Jerusalem, Education in EJ, Israeli Settlements in EJ, the Temple mount, the old city and the Historical Basin and maybe some prospects for the future. If you manage to read through these posts, you might end up having a better understanding of the geo-political issue called East Jerusalem. If in the end of it you have more questions than answers, I have achieved my goal.

—

Many experts and decision makers in the area and around the world believe that there will be no agreeable solution to the Israeli – Arab/Palestinian conflict as a whole, without an agreeable solution in Jerusalem. Despite the critical importance of the Jerusalem Question to the future of Israelis and Palestinians, as well as to world stability, only few really understand what the Jerusalem question is all about. Regardless of their ignorance many hold strong opinions about Jerusalem, which in many cases are influenced more from symbols and the myth than reality. In the words of the Zionist poet Naomi Shemer, Jerusalem is “captive of its dream”.

—

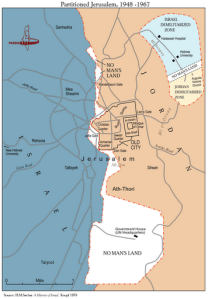

In 1948, when the first war between Jews and Arabs erupted, Jerusalem was one of the main battlefields. The city had the largest amount of Jews in the country, 100,000 out of 600,000 in the whole Jewish Yishuv. There was also a large Arab population in Jerusalem (though the biggest Arab city in 1948 was Jaffa). On top of this, due to its symbolic importance, both sides understood that taking over the city would be a significant achievement for them and a serious moral and tactic strike to the other side. This is why both Jews and Arabs concentrated a lot of efforts throughout the war around Jerusalem. During the first part of the war the battle concentrated on the roads leading to Jerusalem from the west. The Palestinian militia, “the Army of the Holy War” headed by Abd al-Qader al-Husseini, sieged the city by closing the roads leading to it while the Jewish forces, the Haganah militia (soon to become the Israeli Defense Force), made an effort to burst its way in to the city from the Jewish controlled coastal plains eastward towards the Arab controlled mountain. This is how the Jerusalem corridor was created.

By the time the British mandate of Palestine ended, on the 14thof May 1948, the Palestinian militias where crushed by the Jews and Abd al-Qader al-Husseini had died in battle. In Jerusalem the Haganah met the forces of the Arab legion, the Jordanian army. The two armies entrenched themselves facing one another in a line of posts, dividing the city between them – thus creating what later became known as “The City Line”. This line is a part of what is known as the green line, the demarcation lines set out in the 1949 Armistice Agreements between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria after the war. It became the border between Israel and Jordan for the 19 following years, dividing the city in to two parts, and leaving the old city in the Jordanian side.

On June 1967 another war broke out between Israel and its neighbors. Israel attacked first and hit Egypt and Syria, but Jordan attacked Israel… in Jerusalem. Within 6 days the Israeli army occupied the entire Sinai Peninsula from Egypt and the Golan Heights from Syria. The Israeli counter attack in Jerusalem ended up in occupying the entire west bank from Jordan. S

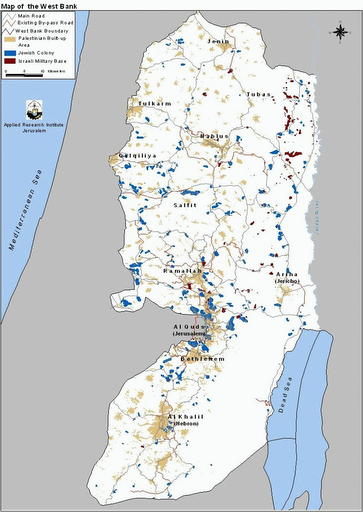

traight after the war Israel made a very clear decision not to annex the Palestinian territories (the west bank and the Gaza strip) because it didn’t want to add millions of Arabs to the Jewish state. This decision still applies today since according to the Israeli law the territories are not an official part of the state of Israel, and that includes the settlements. But even though Israel didn’t annex the territories it made a clear cut decision to change the reality in Jerusalem.

traight after the war Israel made a very clear decision not to annex the Palestinian territories (the west bank and the Gaza strip) because it didn’t want to add millions of Arabs to the Jewish state. This decision still applies today since according to the Israeli law the territories are not an official part of the state of Israel, and that includes the settlements. But even though Israel didn’t annex the territories it made a clear cut decision to change the reality in Jerusalem.

After 19 years of a hostile border cutting through its heart, the Israeli side of the city was in poor condition, and Jordanian Jerusalem wasn’t much better off. From an Israeli perspective west Jerusalem was surrounded by hilltops controlled by the Arab Legion’s artillery. Despite the 1949 Rhodes agreements, Jews were prevented from visiting their holy sites in the Jordanian controlled old city, mainly the Western Wall.

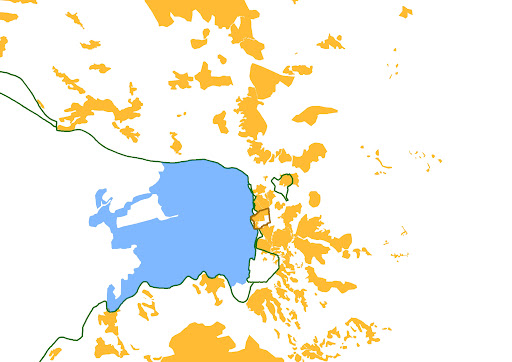

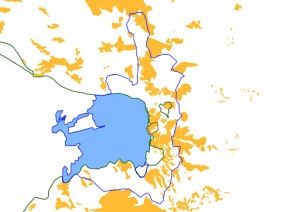

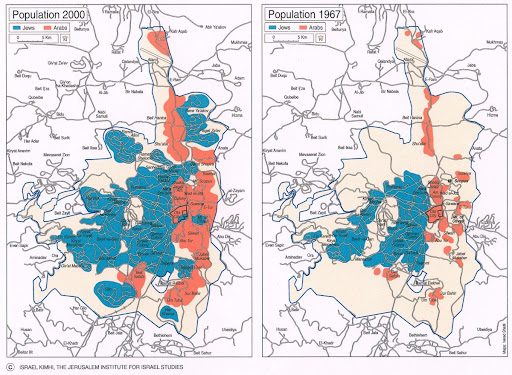

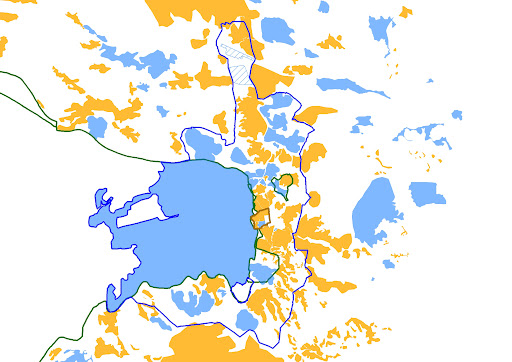

Once the war ended on June 11th 1967, Israel formed a committee to discuss the issue of Jerusalem. Unlike other committees, this one was actually fast and efficient. On June 27 two laws passed in the Knesset (the Israeli Parliament): the annexation of East Jerusalem, meaning that the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration would from now on be applied in these areas. This annexation didn’t restrict itself to the municipal area of Jordanian Jerusalem which was 7 km². The second law enabled the minister of interior, Haim-Moshe Shapira, to expand the municipal border of Jerusalem without the need of a national inquiry committee as usually required when expanding municipal jurisdictions. This enabled the expansion of Jerusalem from Atarot in the north, through the mountain of Olives east of the Old City and all the way to the outskirts of Bethlehem, adjacent to Rachel’s Tomb, in the south. This is how within three weeks from the end of the war East Jerusalem or Greater Jerusalem was created.

In 1967 West Jerusalem (the Israeli side of town) was about 35 square kilometers. Jordanian Jerusalem was, as we mentioned, about 7km², including the old city whose area is 1km². On the ground the creation of the greater Jerusalem meant adding 70 km² to the municipal area of Jerusalem of what had been up to that point a mainly rural area in the west bank. In other words, in the span of three weeks the committee decided to triple the size of the capital, including in it about 70,000 Palestinians, residents of 28 Palestinian villages (including one refugee camp) that were never before a part of Jerusalem.

In this committee there were neither urban planners nor geographers, only generals and politicians. Among its members where the Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, the Minister of Security Moshe Dayan, General Rehavam Ze’evi (a.k.a. Gandhi), Brigadier General Shlomo Lahat (a.k.a. Chich) and others. Naturally what stood before their eyes when they drew the new border of the city was security and politics. The main points where:

1) Defensible borders – back in 67 it meant to pass the border on high places like the Mountain of Olives east of the old city and Gilo to the south. Both hilltops hosted Jordanian artillery officers that targeted West Jerusalem in the 1948 and the 1967 wars. Ze’evi, the military delegate, suggested to create a security belt around Jerusalem in a radius of 15 kilometers to each direction (!) in to the west bank, justifying it by the range of the Jordanian Howitzer canons. The government reduced Ze’evi’s plan only by little, extending the new borders of the city from the outskirts of Ramallah in the north down to the outskirts of Bethlehem in the south.

2) Maximum land – minimum Arabs. The idea was to include in the expanded city as much territory

as possible with as little Arab population as possible. For example Elias Freij, the governor of Jordanian Bethlehem, requested the committee to include Bethlehem in expanded Jerusalem in correspondence with the partition plan 181, stressing that the two cities where never separated throughout history. The committee rejected Freij’s suggestion since it didn’t want to include the 20,000 Palestinian residents of Bethlehem in greater Jerusalem. At the time this division had no physical expression on the ground, no one imagined that a wall will ever separate the two ancient cities.

as possible with as little Arab population as possible. For example Elias Freij, the governor of Jordanian Bethlehem, requested the committee to include Bethlehem in expanded Jerusalem in correspondence with the partition plan 181, stressing that the two cities where never separated throughout history. The committee rejected Freij’s suggestion since it didn’t want to include the 20,000 Palestinian residents of Bethlehem in greater Jerusalem. At the time this division had no physical expression on the ground, no one imagined that a wall will ever separate the two ancient cities.

3) The extension stretching to the north, practically poking Ramallah, was made in order to include Atarot Airport, a small British military airport. There were two motivations for that: first, now that Jerusalem was united again, and this time under Israeli sovereignty as the everlasting united capital, the city was bound to flourish and Tel Aviv would certainly become a mere suburb of Jerusalem. “This is why we need an international airport in the city”. The second and more practical reason was the memory of the Arab siege over Jerusalem in 1948. Areal access to Jerusalem would help to prevent this from happening again. In reality, Atarot was never an active international airport and Tel Aviv has yet to becomea suburb of Jerusalem.

One of the most important decisions that were taken by Israel following the creation of East Jerusalem was to maintain the demographic balance between Jews and Arabs in the city. Based on the census held after the war, greater Jerusalem included in 1967 about 68,600 Arabs and 197.700 Jews. The state of Israel set a goal to maintain a demographic balance of 25%-75% in favor of the Jews. A secret agency called IGUM was set up for a short while in order to achieve this goal. Now let’s stop and think for a moment – how does a state maintain demographic balance anyway? In 2009 the number of Jewish residents of Jerusalem was 497 thousand, while the number of the Arab residents was 275.9 thousand (based on the JIIS statistical yearbook). So while the Jews grew by 250% in Jerusalem, the Arabs grew by 400%. In 2009 the official ratio was 35.7%-64.3% and according to some estimations by 2040 there will be an Arab majority in Jerusalem. Judging by the result, Israel failed to achieve the goal of maintaining the demographic balance between Jews and Arabs in Jerusalem.

The Arab residents of Jerusalem are not citizens of Israel. Usually when a country annex an area seized by force it also gives citizenship to its inhabitants. This is what Germany did in Alsace Lorraineregardless of the oppositionof the inhabitants of that area. But although for a short time Israel gave to residents of East Jerusalem the option of applying for citizenship, it didn’t force it.As a result, 45 years later the vast majority of Arabs in East Jerusalem are not citizens of any country, but hold the status of permanent residents in Israel (though many hold a Jordanian passport). A separate post will be dedicated to the issue of the Palestinian residents in East Jerusalem.

Zionism was never about drawing lines on the map, it was about setting facts on the ground. This is why all along the late 60s and early 70s Israel built Jewish neighborhoods around East Jerusalem. Unlike in the occupied territories, where the settlements policy will be adopted only after the political turnover of 1977 and the rise of the right wing to power, settling Jews in East Jerusalem was the official policy of every Israeli government since 1967. About 30% of the lands in EJ were expropriated in order to build Jewish neighborhoods like Gilo, East Talpiot, Ramot Eshkol, Givat haMivtar, the French Hill and Ramot. Further north Neve Yaakov and Pisgat Ze’ev where built (I don’t include Ramat Shlomo and Har Homa here since they were built after the signing of the Oslo accord, thus I will write about them later on). In Israeli scale each one of these neighborhoods is in the size of a town. Today about 200,000 Jews live in East Jerusalem. Together with 300,000 Palestinian residents of the city the majority of Jerusalemites live in East Jerusalem.

The vast majority of Israelis, including many in the Israeli left, don’t consider these neighborhoods as settlements. In fact many in Israel are not aware of the fact that these neighborhoods are built beyond the green line. The residents of these neighborhoods don’t recognize themselves as settlers and they are not ideologically driven (I grew up in one of these neighborhoods myself). The government used deferent incentives to persuade people to go and live there, targeting mainly weak populations and newly arrived immigrants. This success is an excellent expression of power by the state: it made the people serve its goals without them even realizing it. On the other hand the international community considers these neighborhoods as settlements built beyond the Green Line on land that by international law is considered occupied; the consensus is that the future of these neighborhoods should be decided in political negotiations. As we shall see various proposals for peace agreements tend to reach an understanding that these neighborhoods will not be evacuated in future agreements.

This gap between the Israeli and the international perception of the Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem is important (though bridgeable). There is another type of Jewish presence in East Jerusalem, consisting of small Jewish compounds build in the heart of the Arab sphere. Unlike the big neighborhoods listed above, these are seen by most Israelis as settlements and they do not receive the same level of legitimacy. These small compounds are mostly private initiatives strongly supported by the state. They are guarded by private security funded by the Ministry of Housing at a cost of tens of millions of shekels a year and they are settled by ideologically driven setters mostly affiliated with the Israeli religious extreme right. I will dedicate a separate post to these settlements and their effect on the ground.

No country in the world apart of Israel accepts the annexation of East Jerusalem. In fact, the world did not acknowledge the Israeli sovereignty over west Jerusalem or the Jordanian sovereignty over the other side prior to 1967 (only England and Pakistan accepted the Jordanian sovereignty in Jerusalem). The last international decision regarding Jerusalem was taken in 1947 in the UN 181 decision. In it Jerusalem receives a status of Corpus separatum – an international area. Regardless of the fact that there is no successful example of this idea around the world, it is still the official position of the EU and there is an ongoing debate over this in the US government. This way or the other, history has taught us that so far it is not the UN decisions, but rather the soldiers on the grounds that shape the reality. Not even Israel’s best ally, Micronesia, acknowledged this Israeli policy. Not to mention its obvious supporter – the United States of America. For this reason today there is not even one foreign embassy in Jerusalem, the everlasting united capital of the state of Israel. Moreover, some countries keep a consulate in Jerusalem that function as an embassy to the Palestinian authority.

After 1967 the separation between East and West Jerusalem on the one hand, and between East Jerusalem and the West Bank on the other hand, was mainly virtual. It was a line on the map. For the Palestinians it also meant the color of the ID, certain benefits to the Jerusalemites and being subjected to different systems of law. But in general there was freedom of movement and the separation wasn’t felt on a daily basis.

On the political level Jerusalem always remained on the agenda. Despite Israel’s disapproval the Jerusalem issue kept coming up. Already in 1970 the US president Richard Nixon offered to divide the city. During his historical speech at the Knesset, the Egyptian president Anwar Sadat mentioned the Arab obligation towards Jerusalem by saying: “The holy shrines of Islam and Christianity are not only places of worship but a living testimony of our uninterrupted presence here. Politically, spiritually and intellectually, here let us make no mistake about the importance and reverence we Christians and Muslims attach to Jerusalem.” In 1980 Israel legislated the Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel, in an act that halted the autonomy talks with Egypt in which the future of Palestinian Territories and Jerusalem were discussed.

In December 1987 the first intifada erupted in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. It was a popular uprising that spread throughout the Palestinian territories occupied by Israel in 1967. The Palestinian citizens of Israel, also called the Arabs of 1948, did not take part in the uprising. But Jerusalem, that remained an inseparable part of the occupied territories, did. More than this, the intifada was to some extent managed and shifted from Jerusalem. Among other things this marked the failure of another Israeli goal in East Jerusalem – Israelisation of the Arab Population. The eruption of violence in the Arab parts of the city brought to the surface for the first time since 1967 the division of the city. It wasn’t only that Israelis had stopped going to eat hummus in Arab restaurants, but some municipal services were actually interrupted and state symbols where attacked. The violent uprising in East Jerusalem was a water shed line: for the first time the city was divided from below, by its people, by the geography of fear.

The next chapter will deal with Jerusalem in the peace process with the Palestinians, from the Madrid conference of 1991 and the Oslo accord (1993) all the way to the Camp David talks in 2000 and the eruption of the second intifada. It will end with the construction of the separation barrier in the city, called the Jerusalem Envelope.